Carla Tomasi, a cook who loved to teach.

The cook, chef and gardener Carla Tomasi, who died in Rome last month aged 70, was a trailblazing chef, and a single minded and beloved teacher. The following is about her life.

This is the reason I started a substack. It started out as a 700 word column for The Guardian, but soon outgrew that. It is thanks to conversations with Maxine Clark, Martin Saxon, Sara Saxon, Peter Gordon, Killian Fox, Lucy Antal, Andrea Locci, Agnes Crawford, Thane Prince, Hande Leimer, Francesca Bruzzese, Stefano Arturi, Matt O'Callaghan and Alice Carosi-Adams, also online friends and colleagues, to whom Carla was devoted. I am grateful to my friend, the photographer Sophie Davidson for allowing me to use her portrait of Carla and to The Guardian Newspaper, Tim Lusher and Anna Berill for permission and help in expanding a column into this 4400 word essay, so an average reading time of 15 minutes, which is more or less the average drinking time for a pint.

•

•

It was autumn 2013. A friend mentioned ‘Carla’ who preserved what she grew in her garden on the outskirts of Rome and had an intriguing past as a chef in Soho. Curious to know Carla, her jams and her pickles, I wrote her an email. A reply arrived almost immediately. It included several direct questions and an invitation to lunch.

The automatic green gate didn’t work; you had to call, wait, then after a bit Carla would come down and lead you up the drive that ran beside her largely edible garden, to the white chairs on the veranda in front of her house. It was a humid day, I remember, so she encouraged us, my partner and I, to spray our ankles with mosquito repellant before we walked around the garden, and as we did she pointed out plants, and cats - Cipollino! Cirillo! Mr Big! - that were variously arranged in warm spots. Sitting on the wooden chairs around her long table, we ate focaccia not-long-out-of the-oven and pickles, borlotti bean soup, baked fish with rosemary potatoes. To finish, she brought out three Tupperware tubs of ice-cream. ‘All recipes from David Lebovitz’s book the Perfect Scoop. Let’s hope they live up to the title’ she said as she dipped the metal scoop in water.

Conversation came easily and we talked about London pubs in the 90s, Anna del Conte and Jane Grigson, the beauty and the horror of Roman trattoria food ‘Deep fried artichokes! Cremated artichokes more like!’ and how to pickle courgettes. Four hours later I left with a bunch of sage so big and pungent we needed to roll down the car windows, and an insulated Lidl bag full of vegetables from the garden with instructions, ‘Don’t put the tomatoes in the fridge. Eat that aubergine first, and the lettuce tonight.’ I had met Carla.

Carla on her Veranda in October 2018, taken by Sophie Davidson for the Gannet.

Carla Tomasi was born in Rome on 9 May 1954, the daughter of Antonio Tomasi and Onorina Mercuri. She had a sister, Selma who was older by seven years. Rome in the late 1950s was in the midst of huge urban growth, new housing filling the outskirts of the city, the newly inaugurated Metro redefining it. The Tomasi’s, like many families, moved from an apartment in the center (San Giovanni, we believe) to a house with a veranda, garden and garage, in a suburb called Bagnoletto Dragona, not far from the archeological site of Ostia Antica and a few miles from Lido di Ostia, the only district within the municipality of Rome on the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Her father Antonio was a keen gardener, grew vegetables and hunted, while her Grandmothers, from Sardinia and Le Marche respectively, were both good cooks: all three shaped Carla. It was the terrible and careless cooking of her Mother, however, that drove Carla into the kitchen. She was about 10 when she said to her mother ‘Shall I do the shopping? and her mother replied ‘Oh my god, a child of mine that wants to cook’ and gave her some money. So Carla started to do the shopping, and use the oven, to cook and cook. She also persuaded her parents to pay for a subscription to the magazine Homes and Gardens, which at the time included a food supplement called à la Carte, a glossy escape from what she described as a secure, but not particularly happy childhood.

Carla, aged 4 or 5 with her sister Selma and parents Onorina ‘Nina’ and Antonio. With thanks to Francesca Bruzzese

There are a few, fleeting things Carla said over the years that fit here. Catching the trenino that connects Ostia with the center of Rome in order to go to liceo high school. Eating pizza rossa and smoking on the grassy verges that surrounds what was once a chariot-racing circuit at Circo Massimo. Hating the smell of the chicken broth served at what seemed like endless family funerals; her father leaving with a fishing rod and coming home with a trout; extra english lessons ; riding the number 13 tram and a man flashing; going to Cinema Metropolitan di via del Corso

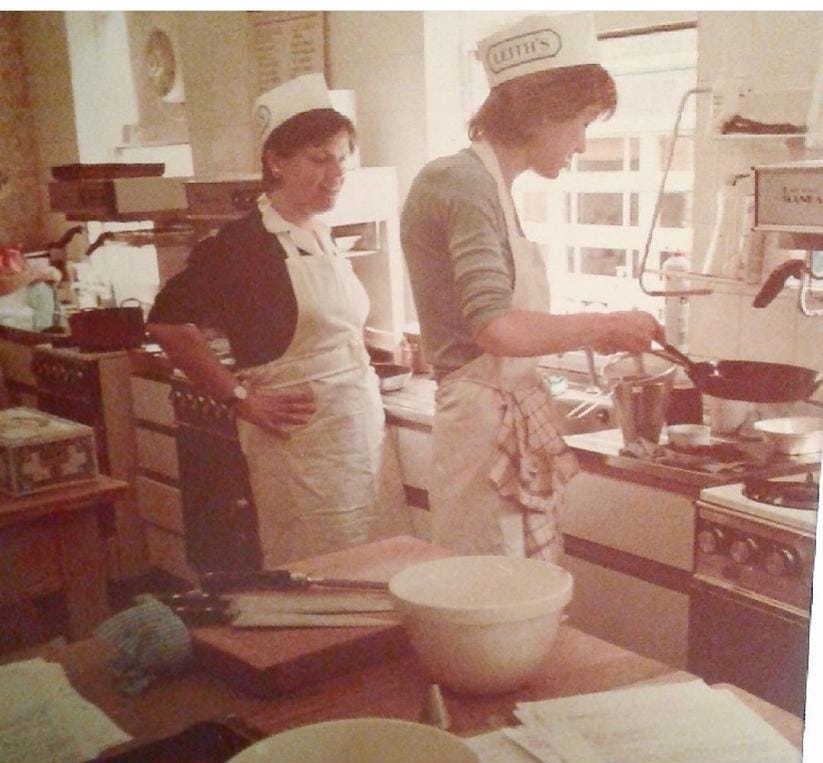

In 1972, just turned 18, Carla did what she always said she would do, and 'bolted' for London. She found work as an au pair to begin with: an ideal situation in which to improve her already proficient English and to put into practice the English- style baking she had long been curious about. Various jobs followed, in both Rome and London, Carla increasingly certain that she wanted to be in a London restaurant kitchen. The way to ensure this, she decided, was a diploma from Leiths School of Food and Wine in West London. Having persuaded her mother to contribute to her fees, the year-long course began in September 1981. One of the tutors that year was Maxine Clark, who remembers Carla as serious, determined, and slightly terrifying, also her own curiosity as to why a hugely capable 27 year old Roman cook wanted to study classical French cooking, in London, under the tutelage of a Scot. Although later Maxine would understand these were exactly the sort of unique circumstances Carla enjoyed. Carla graduated with distinction in July 1982.

Carla with another student at Leiths in 1981 or 1982, with thanks to Maxine Clark

Her first job lasted barely two months, and resulted in her being banned from the premises by Antonio Carluccio, a story she told defiantly. Brevity meant that she was able to take a job at a restaurant called Frith’s on Frith Street in Soho, first as a chef, later taking over the running of the place. Restaurateur Martin Saxon, who was working nearby at the time, remembers Frith’s as having ‘Just a few tables, simple decor and a small menu - four starters, four mains, that changed regularly’. It is also true there could be as many as 10 puddings, because, she loved puddings. With Carla leading the kitchen the emphasis leaned more firmly towards things Italian, but the french influence was decisive. Saxon remembers the Lamb tartare, which was also appreciated by Alistair Little, whose eponymous restaurant was a few doors away.

It was Carla who gave a young chef newly arrived from New Zealand, his first job in London. The chef was Peter Gordon, and describes starting at Frith’s like ‘Entering another world, part Fantasy, part dictatorship, with bizarre systems but hugely loyal customers to Carla and her cooking’ and Carla a ‘Fabulous chef with mercurial moods.’ Gordon remembers preserving whole lemons in olive oil, sweet pickling sardine filets and making a chestnut flour and rosemary flatbread called Castagnaccio. We have another detailed record of Carla’s food at Frith’s thanks to a review by Kingsley Amis for The Spectator with the heading ‘Blissful fare in Soho’. The page long piece notes just one shortcoming ‘The wood pigeon that wanted a little more chewing than was proper’ and waves of praise for the ‘Impeccably cooked liver’ and ‘Beautifully cooked fillet of beef with green sauce,’ and gooseberry fool that was ‘Out of this world’. Amis ends his review with a note about the service. ‘Not only efficient but that of a special friendliness that is possible only in a small place where everyones wants you to be pleased.’

Carla would describe her years at Frith’s as happy and adventurous, also unpredictable, and Soho at the time - alongside Alistair Little, Anthony Worrall-Thompson, and Jeremy Lee - as ‘Volcanic.’ Also volcanic was the doubling of rates imposed by Thatchers Government in the winter of 1990, which would tip them into liquidation. The photograph below, of Carla wearing a red jumper and dark blazer in front of Frith’s, captures her at the beginning of that adventurous and mercurial time. It was taken in 1984, so she was 30. For many, Carla was part of what publisher Tom Jaine described as ‘The spurt of energy that revolutionised UK food in the 1980s and created Modern British cooking’ which saw cooks looking beyond the Anglo-French model to the methods and dishes of other cuisines. When I talked to her about all this, asked her what she thought she contributed to the London food scene at that time, her answer, after laughing, was ‘Vegetables, well cooked vegetables’.

Carla outside Frith’s on Frith Street in 1984.

After Friths, Carla began teaching at Heidi Lascelles Books for Cooks in Notting Hill, producing cookery cards for Safeways supermarket and writing occasional columns for Country Living. The food justice campaigner Lucy Antal was Carla’s assistant during this time, and remembers her as a highly intelligent and volatile creative force and the hedonistic entertaining at her Judd St, Art Deco Flat. Lucy still makes the Ethiopian Dersa lentils that were a favourite at Books for Cooks, and that Carla very likely learned from her Italian-Ethiopian lover at the time, Claudio, with whom she had a tempestuous affair and spoke of as the love of her life, and who died young.

The early nineties also saw the beginning of a collaboration and lifelong friendship with Sara and Martin Saxon, and later Sarah Roberts, when Carla began teaching on their Tasting Places cooking courses. The market-led, improvisational cooking suited Carla, as did teaching, She also seized the opportunity to expand her knowledge: the food of Rome and Lazio she knew, also the customs of le Marche and Sardinia, but beyond that, the food of the other 17 regions was still quite mysterious. The courses, held all over Italy, changed that. She would refer to time spent in Menfi in southern Sicily, alongside Maxine Clark, as the happiest of times and carried recipes and memories like souvenirs - chickpea flour panelle, fish couscous, cigarette breaks with max, vegetables braised lemon and oregano, a hot dust-laden wind called sirocco, how best to fry tubes of cannoli. Sara Saxon remembers the experience and intelligence that defined Carla’s teaching, the ease with which she turned a hands-on lesson for 17, into dinner. Also how Carla, blatantly ignoring parental wishes, bought Sara’s two year old son a pair of red patent shoes from Palermo Market, which he then wore until they could be worn no more.

Carla and Maxine Clark enjoying a moment of rest between lessons, during one of Sara and Martin Saxon’s Tasting Places cooking weeks in Sicily.

In late 91 or early 92 Carla agreed to lead the kitchen at the Peasant, an old boozer that had been converted into one of the first Gastropubs of its kind on St John Street EC1. In her review for The Independent in 1993, Emily Green describes The Peasant as ‘A glorious big shell’ and Carla ‘A most uncompromising, idealistic and earthy chef who cooks real food with the best of ingredients, vividly flavoured, distinct in texture and generous in quantity.’

The Sardinian chef Andrea Locci was part of Carla’s Italian, Moroccan, British-Chinese, Welsh brigade at The Peasant and remembers some of the dishes on the handwritten daily menus - Mozzarella and Parmesan fritters with chilli jam, spinach and ricotta dumplings in tomato broth, Thai chickpea curry, grilled lamb with potato and rosemary cake, monkfish with tomatoes, oregano and olives, squid and chorizo stew, white chocolate and lime semifreddo, banana and amaretto fool. What a list! Revolutionary even, for a London pub at the time. And Banana and amaretto fool sounds the sort of playful delight that was so typical of Carla.

The Rome guide Agnes Crawford grew up in Islington, and ate at The Peasant when she was 14 or 15. She remembers the mismatched furniture, candles and chunky plates feeling simultaneously rustic and chic, and how, for a slightly gauche teenager, Carla’s Italo-Londinese sausages and beans tasted like adventure and possibility. Friends from that time all agree: at The Peasant, Carla came into her own, her great skill invested in homely good food that reflected her culinary roots and her curiosity. She was notorious for asking everyone who walked through the kitchen door ‘What does your mother cook?’ And if she liked the answer, putting it on the menu! Which is also funny, knowing what we know about her mother!

Carla and Andrea Locci, in 1994

When Carla moved to Terence Conran’s stylish and canteen-like Habitat Table Cafe on Tottenham court road, so did Andrea Locci, in order to head up the new pastry section. Together they pooled their knowledge of regional Italian desserts and the icon Raffaella Carrà, discussed the state of Italian politics. ’Carla was an innate teacher’ he tells me in elegant English with a just discernible Sardinian accent ‘And my culinary mother’. He also recalls her need to laugh and party, that when Glamorgan sausages were on the menu at The Peasant, they were written as ‘Glamorous sausages’ and served with raisin and apple chutney.

•

Carla returned to Italy in 97 or 98, during which time she was also teaching cooking courses, so moving around constantly. In an interview we did together for a magazine called the Gannet, she was emphatic: she loved London, but at 43 it was time to leave. She found a flat in Ostia, so a good few miles from the family home and about 20 miles from the centre of Rome, and started making bigger plans, speaking to friends about a family house and land in Sardinia that could be the place for the cooking school! Plans changed abruptly. In 2001 Carla’s father Antonio died, and almost simultaneously her mother’s increasingly odd behaviour was finally diagnosed as Dementia. Even more abrupt was the death of her sister Selma. In the midst of this shocking loss, Carla would leave her flat in Ostia, and move back to Dragona in order to take over the care of her mother, with whom she’d always had an extremely difficult relationship. Three harrowing years would pass before her mother died, in 2009. Carla was, quite simply ‘Surrounded by death.’ I feel I can write all this, because Carla spoke quite openly about this time.

•

Ripping up the paving stones her mother had laid in front of the house in order to create a garden was Carla’s response to unimaginable times. She was assisted by her partner at the time, Andrea, who was a capable builder and garden companion. Teaching continued intermittently, but Carla would become increasingly reclusive as she poured all her energy and attention into her 20 x 20 m garden, moving enormous amounts of soil, cultivating an edenish exuberance of vegetables, fruits trees, shrubs and herbs, and taking in a colony of cats who made themselves at home amongst the plants.

Years passed, and the garden and colony grew. The word Agoraphobia is derived from the Greek words ἀγορά, a place of assembly or market place, and -φοβία, fear. When things had changed, Carla joked that fear of the market place was an unfortunate disorder for a cook who needed to fill her pink trolley. She joked, but never hid how difficult life was, how afraid she was of her deep-seated unhappiness and black corners. Andrea was a supportive (and well fed) partner during this time, but he also spent long periods in his native Poland. Prolific e mail correspondence with old friends, permaculture and food preservation forums, seed sharing, and twitter became her means of communication. As did nascent instagram, which she would come to use with spontaneity and wonderful disinhibition. ‘The garden saved me’ she would say, later, ‘But social media was my way back into the world.’

Carla and me, in her garden, in 2018, by Sophie Davidson

In the months and years following our first e mail and lunch on the veranda in autumn 2013, Carla and I would become friends and she would become my teacher, inspiring dozens of Guardian columns, and contributing to books - no one has influenced me more. Although you only needed to cook with her for an afternoon to realise that Carla was also a front-row student, just as interested in how everyone else did things. Even with dishes she’d made for decades, if someone had a way that improved it, she would gather it up like a snowball rolling down a slope.

The first collaboration was a bake sale at Alice Adams newly opened Latteria studio in December 2015 for which Carla made no less than 20 Jane Grigson Christmas cakes and a dozen different preserves including Onion and fig marmalade, tomato chutney, plum and pomegranate chutney, pickled courgettes, Indonesian cauliflower pickle, apricot jam and chocolate and pear spread. What happened next was a case of good timing. Carla was ready to teach, Alice had a studio, I was writing and we were all part of an online community: in 2016 we came together for ‘Market to table, cooking days, much in the spirit of the Tasting Places courses that had gone before. Carla would pick whatever was ripe in the garden and pack it in her trademark pink trolley, while a group of us went to Testaccio market to get everything else, then we would all meet at the studio kitchen and turn the lot into lunch.

Carla would also teach her own ‘Cooking with Carla’ lessons at the studio, and record the cannelloni episode of Vicky Bennison’s hugely successful Pasta series. Market to table, though, was our place of assembly: wonderful because it was noisy and collaborative, wonderful thanks to the people who came. We would cook a great number of things, serving them on up on the innumerable plates in Alice’s studio, or the smart serving dishes Carla inherited from her mothers shop - fried things, two sorts of focaccia, fresh pasta, baked fish or braised meat and pudding. Not forgetting ‘several’ vegetable dishes, the part Carla enjoyed most, and why we called her a “vegetable whisperer” a joke that became her hashtag. We brought wines from Antonio at Les Vignerons. ‘The cloudier and wilder the better’ she would say, sniffing but never drinking, noting she had done more than enough of that. On the occasions she had several back to back lessons she would leave the studio making it clear we wouldn’t hear from her for few days, because she needed to be in her garden: it was both her retreat and a form of regeneration.

Carla and Alice Carosi-Adams in Carla Veg patch, 2015

The garden was her solace, but the kitchen was her place: she moved around it so well. As she pressed focaccia into a tin, trimmed artichokes until they looked like skinheads, salted pork cheeks in order to make guanciale, or pulled sheets of pasta from between the rollers, her hands captivated during lessons, while her steady stream of knowledge and advice filled the room. The advice, though, was always taut, sometimes so much so it could feel like an admonishment. And sometimes it was an admonishment, which she was equally happy to receive. Alice and I saw it as a sign of our friendship that she showed us her temper, to glimpse her mercurial moods.

Carla was full of sentiment but not sentimental, and never mawkish about food or techniques: championing products - frozen pizza, gravy granules, custard powder, instant mash as a thickener, and machines that alleviated the burden of cooking. Ideas like ‘Italians do eat better’ were swatted away like irritating flies, and while she celebrated Italian food she never fetishsed it, nor mothers, or grandmothers, despite having had an extremely capable pair of them. ’Non sono una signora, una con tutte stelle nella vita’ I'm not a lady, one with all the stars in life, she said more than once, quoting the defiant song by Loredana Bertè.

Alice and Carla at the first Latteria studio, in via Ponziana, 2017 (I think)

Friends who had known her for decades said she softened over the years, although not her humour, which oscillated between silly and dry. Nor did her provocative often funny statements about things or people she thought were ridiculous, hurled like small grenades into the middle of lessons. Memorable was her reaction to an American chef who hand-rolled pasta. We were at the studio, sheets of pasta rolling out of the machine, when someone told her about a chef, with a beard, whose surname was Funke and whose motto was ‘fuck your pasta machine. She paused, smoothed the sheet of pasta and said something long the lines of ‘I have one thing to say to Mr Funky, and that is fuck you! In such moments there was glint in her eyes, leaving just enough room for interpretation.

Behind the entertaining grenades were strong principles. After the lesson she took to instagram for one of her ‘effing rants,’ defending the pasta machine as an indispensable and democratic kitchen tool that had liberated women like her grandmother (who rolled pasta until it was the size of a table). Full of exclamation marks and dashes, she called out the notion ‘That-pasta-with-a-rolling-pin-was-holier-than-yours’ and somehow better than machine rolled pasta (it isn’t, they are simply different) and lambasted ‘Food as a cult.’ It was a specific rant, but also a wider example of her democratic, unpretentious beliefs about food. Of course none of this stopped her admiring hand rolled pasta and those who possessed the skill to do it (I reckon Carla and Mr Funke would have got on). She also declared 12th January International Pasta Machine day. It still is.

Carla and her ‘effing' pasta machine, with thanks to Anne and Don Hesleton

Some of her most generous teaching was during the pandemic. When the world went into lockdown, Carla was one of the first to open up her computer in order to host hours of free cooking lessons and virtual chats; Sometimes with a theme ‘making the most of your freezer’ (there were few things she didn’t freeze) or ‘batch cooking 101’ often co-hosted with friends Stefano Auturi and Matt O'Callaghan; other times she simply provided a space to talk

Not forgetting the innumerable text and voice messages she sent all over the world. Her white table-desk was in the middle of her narrow dining room, near the wood burning stove and next to a dresser stacked with some of her favourite books - Anna del Conte’s Gastronomy of Italy, Jane Grigson’s Vegetable book, Paula Wolfert’s The Food of Morocco, Honey&Co, Le Ricette Regionali Italiane, Jeanne Carola Francesconi’s La Cucina Napoletana, Jenny Chandler’s Pulse, Thane Prince's Jams & Chutneys, Dan Lepard’s Short and sweet. She would sit, a pillow in the small of her back, typing advice or recording steams of thoughts: she was as devoted to her online community as we were to her. She had mixed feelings about writing a book, starting, but then stopping with the excuse it was overwhelming and made her cross, and that she liked that her recipes were free. And they are. Her glorious and pragmatic instagram account is an archive of her immense knowledge. It’s a resource that must be protected at all costs.

The cook and teacher Stefano Auturi describes her as ’An egalitarian who hated food snobbery and saw her knowledge and advice as a counter-act, so felt compelled to share’ also a fabulous gossip who loved a good laugh. I found her attitudes to food and teaching political; her immense frustration at laws and rules so completely at odds with the welfare of most; her belief that food had both a higher purpose and a responsibility to educate and inform, although she would never have been so pretentious as to put it like that! Francesca Bruzzese, with whom Carla was close, remembers her personal kindness and generosity with time, also an almost comical Whatsapp response time: she was rarely more than seconds away from answering any cooking query, often signing off with her signature ‘boom’. Both Francesca and Stefeno said the same thing, that it feels quite unbearable to know there will will never be another message saying ‘Buongiorno from the ‘burbs.’

Carla’s with her raised herb and salad tables (amazed there isn’t a cat in one of the pots), in 2023, with thanks to Agnes Crawford

Carla confided in friends that coming out of the pandemic was even harder than being in it, how her anxious spirit and struggle was exacerbated by other circumstances. None of which stopped her tending her garden (‘you have to water before the sun hits’) or cooking with care (Andrea Locci puts it well. ‘Carla cared to bring out the best in ingredients and knew the power of simple good food.’) She also finished her years-long project of converting the living room into a teaching kitchen, with shelves for her favourite ceramics, many made by Martin Saxon and Gabrielle Schaffer. She was especially pleased with the central table which meant 12 could participate in a lesson, and then – once a cloth was in place - sit down for lunch. She held her ‘Long table lunches’ there, gave 30 or so lessons, and had many more planned.

It is a great kitchen, airy and luminous, which is why she asked her carers to bring her bed down (the pathos was not lost on her) so she could rehabilitate looking onto the garden. She was recovering, it seemed (she could be exasperatingly evasive) although not enough to fight an infection. During her last weeks she was surrounded by friends.

•

When Carla, aged 10, asked if she could do the shopping and use the oven, she discovered that she loved to cook. That never changed. Carla Tomasi loved to cook. She needed to cook, and later to teach. Throughout her life, as a chef, restaurateur, teacher and friend, she sent thousands of recipes and lessons into the world and now those recipes and lessons are part of thousands of lives and destined to be repeated again and again. Carla also brought people together, or maybe herded is a better word, in the kitchen, at the table and online. So much so, that we remain herded together, in our feelings of sadness that she has gone; gratitude for what she shared; and in the knowledge - and of this I am certain - she will be more alive than ever in our hands when we shove rice into a hollowed out tomato.

And years from now, someone who has never heard of Carla Tomasi, will eat a slice of focaccia that has been pushed to the edges of the tin with a particular dabbing-stretching movement because years before someone else watched Carla do that movement, admired her fingers, wondered about her stamp-sized wrist-tattoo. Someone who maybe heard her say (she had a lovely voice) ‘If it keeps springing back, it needs further relaxing, so leave it to rest for a while’ which is good advice for focaccia, but could just as easily be advice for life.

Carla Tomasi, 9 May 1954 - 22 August 2024

Carla on her Veranda, in October 2018, with a tomato timer so she doesn’t forget the focaccia in the oven, taken by Sophie Davidson

Just a lovely tribute to her life and her life’s work . I cherish her voice messages on my insta messages , when every odd query would get a prompt , encyclopedic response .

Shopping with her at the market was a lesson in roman cooking , simplicity and deliciousness.

I only knew her late in her life meeting in that market one day , in 2019 , Rachel you rendezvoused there for a brief hello before we took to wander through the stands . After we had a lunch with her at Marigold , I met Francesca that day as well .

She declared “I never travel

I won’t travel .. “ she disclosed much about her likes and dislikes of cooking at that lunch and her wit was as acerbic as her criticisms .

I mourn the loss of her lessons , and knowledge .

It was a shock to read her open honest posts of some of life’s challenges , and so typical to read her posts on the state of the horrific hospital food , towards the end ..

Of course I don’t know it was the end .. I’m not sure what I thought , but the news of her death struck me hard .

Terribly saddened I’ve reacted in part by listening again to those messages she’d leave , and reading all these remembrances of her recounted by this large community of cooks and friends .

Thank you for detailing her life a bit and giving us readers a glimpse into the experiences that formed her brilliant perspective .

Oh Rachel, this was perfect.

It made me smile, made me cry. ❤️